What exactly is a

Story Artist?

a Story Artist is half ‘director’, half ‘screenwriter’.

That’s the best summary I’ve heard. We can’t call it either though for guild/studio reasons, so it’s Story Artist. Essentially a bridge between writing and directing. The core skills of the job are:

Filmmaking

Screenwriting

Storyboarding

Pitching

The foundations of my own storytelling career are rooted in being a Story Artist. It can be one of the most creatively challenging and rewarding jobs there is, but if you’re unclear what a Story Artist even is, you are far from alone! Despite how ubiquitious it is and how long it’s been around (right there at the top of the credits after the voice talent of animated films), it’s still a surprisingly vague and engigmatic profession. Here’s how most conversations about it go:

CURIOUS PERSON

Ah, so you’re an animator?

STORY ARTIST

No. I mean, it’s for animated movies, and we know how to animate traditionally but-

CURIOUS PERSON

So you draw the movies?

STORY ARTIST

Kind of.

CURIOUS PERSON

So you write the movie?

STORY ARTIST

Kind of.

CURIOUS PERSON

Well, which is it?

STORY ARTIST

Both. But also neither?

LESS CURIOUS PERSON

What do you make?

STORY ARTIST

Story pitches. Writing with Storyboard sketches then pitching them.

CURIOUS PERSON

Storyboards! Ok so you draw the shots.

STORY ARTIST

Not really, that’s the cinematographer.

BARELY CURIOUS PERSON

(Sigh) What, on that final film do you make?

STORY ARTIST

The story.

NO LONGER CURIOUS PERSON

…I don’t get it.

STORY ARTIST

It’s ok, nobody does.

It’s simultaneously all things, and none of them. It’s helping to write a story, develop character personas, design how to tell it cinematically, and pitch those directions and plans in presentations so each department can reference to see how they fit into the whole. The job is a mix of responsibilities at the crossroads of many departments, primarily writing, directing, editorial, animation, art, and layout (Cinematography). It’s often lumped in with “Storyboard Artist” which, while storyboarding is definitely part of the job - it’s certainly not all of it. I’ve also heard it called “Sequence Director”, and then the Head of Story as “Story Director” which is probably clearer.

Any of the planning, re-writes, blocking, multiple takes, that happen in live action, can’t be done in animation. So, we do all of that in story. Whatever needs to be done to get the story created, told, vetted, and ready for production, story artists are there to have everyone’s back filling in the narrative gaps so we can keep laying track for a production train that’s coming whether we’re ready or not!

In games, this is similar to the role of narrative designer, emerging for many of the same reasons Story Artists did, except that instead of a foundation in game design, a story artist has a foundation in filmmaking. Instead of game-writing and grayboxing, you are screenwriting and sketching.

Story Artists are Screenwriters…who also sketch.

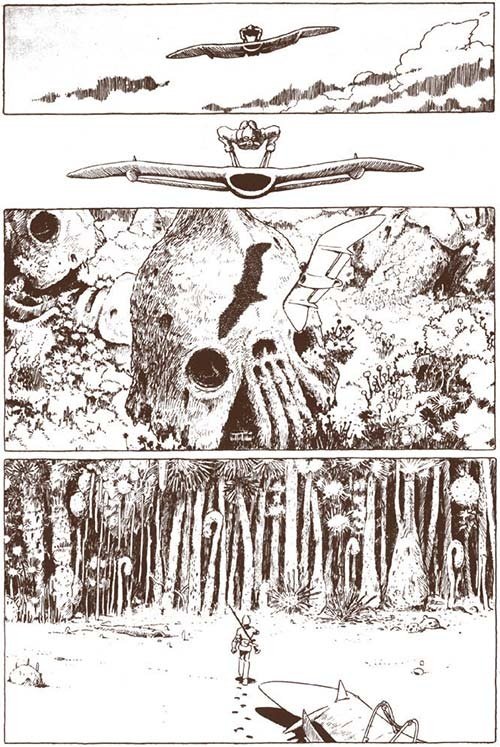

“Just making pictures”. The nature of the screenplay deals in pictures, and if we wanted to define it, we could say that a screenplay is a story told with pictures, in dialogue and description, and placed within the context of dramatic structure. That is its essential nature, just like a rock is hard and water’s wet.

Syd Field, “Screenplay”, 1979

Story Artists are screenwriters who don’t limit their writing to typing. The word ‘screen’ is right in the title! You know what you call a writer who doesn’t write for the screen? A writer.

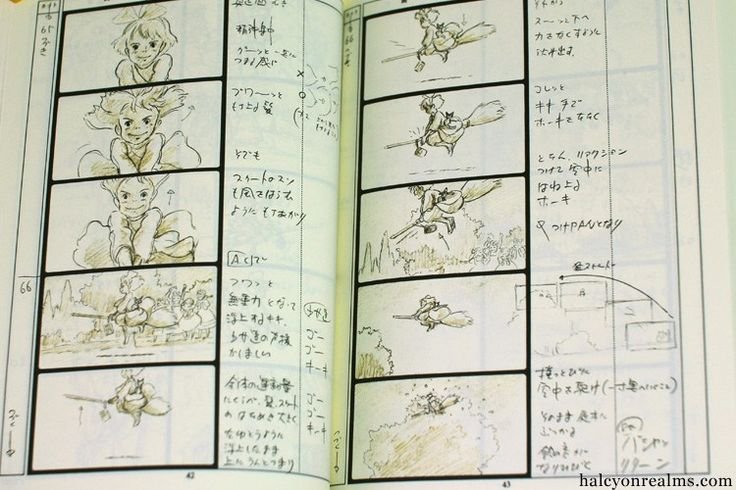

Hayao Miyazaki, is probably the most prominent example of this method.

Screen-writing came about as a way for people who couldn’t draw, to write visual stories meant to be told on a screen as moving pictures and sound. Story Artists just swap out typing text & table-reads for handwriting, sketches, and story pitches.

Joe Ranft used to tell us our job was simply to “clearly pitch and sell the scene by any means necessary. Eventually it needs to be a story reel, but when you’re writing and conceiving it, do whatever it takes to communicate that to the room”.

Storyboarding "The Process!" (in rough storyboards) by Joe Ranft

To be clear, screenwriting is great and an artform unto itself (I like it too), and very important part of the toolbox, but far from the only tool, or best way to write visual stories.

Can a great screenwriter describe visuals? Absolutely! Is it clearer to actually ‘see’ those visuals instead? Of course! Less translation tax is always clearer. There’s just fewer people who can do both, and being the smaller group you often end up lost in the noise of the far larger pool.

Story Artists spend most of their time designing and solving the same character, world, and structural arc problems a screenwriter does, but then also the Cinematography, Pacing, and Acting a Director and Editor are overseeing. It’s just easier and clearer to convey how all of this works in harmony by pitching sketches, than reading pages.

Why Story Artist vs Screenwriter?

Again, I want to stress that this is not a ‘which is better’ thing. I love screenwriting too, it’s obviously a well established art form that requires a very specialized form of writing. Also, screenwriters are often my favorite people to talk shop with because we have weird jobs most people don’t get and if I didn’t have other writers to talk to I would turn to stone, or melt into a puddle of ink.

Sketching is simply not an option for the majority of screenwriters because not everyone draws, and for many films that’s enough! If you have live actors to fill in the character blanks with their own personas to start with, you don’t need to ponder, design, and sketch every beat of those choices required for a take of a performance. Writing exists for a reason, it’s faster, easier to edit, and cheaper!

That said, thinking everyone’s on the same page only to find out they’re not once the money hose of production is running is anything but cheaper, not to mention destroying confidence in the project’s leadership, and deteriorating morale that often feeds into an unfortunate spiral of burn n’ churn. So, how do you decide when you need the additional clarity of a story artist or not?

CLARITY

Walt Disney invented this role at his studio to solve the problem that screenwriting wasn’t enough to clearly convey what was going to happen, for animators to work effectively. In live action you could write, re-write, and make big changes during the shoot, then later do re-shoots as well. Animation is simply too time consuming and labor intensive to do that, and there is an impossibly broad range of translating text to visual you can’t do on the day like you can in live action. This is also one of the reasons a story artist does rough sketches, and not cleaned up storyboards.

PLANNING AHEAD vs DURING FILMING

Imagine all of the writing, storyboarding, planning, blocking, acting, edits, re-writes, dialogue tweaks, multiple takes, and re-shoots that happen in the process of filming from pre-production through production. That’s what the story department’s story artists are doing for an average of 3-4 years ahead of production per picture. Figuring out the story, and how it’s told before opening the money dam of a production budget.

We make the movie, before We make the movie.

This process is being adopted more and more by live action as well, the bigger the budgets get because once a filmmaker realizes what this process allows them, there’s really no going back.

ABILITY TO SELL A/V STORY IDEAS

Relying too much on visuals can of course lead you into films that meander and lose focus. On the flip-side, over-reliance on text is often when things most often become glib, and start to lose the reason it’s told cinematically, instead ending up a 3-cam version of a radio play.

When you write in the language of your medium, you can do the things that text simply can’t convey as effectively, so of course new ideas emerge and scenes become reimagined and re-written by story artists all the time. Editors need footage to cut and review. We create that footage by doing a hybrid job at the crossroads of director, writer, actor, and editor all complementing one another, woven together into a pitch that previews the film in a cost effective, iterative friendly manner. Our sketches are the visuals, and our pitches the audio and dialogue.

Reducing Creative Misinterpretation

Another reason is that film is an A/V medium. Give 8 artists the same script and you’ll get 8 different interpretations of it. Ex: BMW Films launching 8 outstanding storytellers to create a short film from the same launch and script page. Pixar runs a similar training program for Story Interns to develop and pitch to the Story Artists for feedback.

Story Artists finalize their sequence as storyboards to reduce creative misinterpretation you get from relying solely on scripts. Working in collaboration with editorial, we cut together story reels that convey a far clearer direction of telling the story cinematically.

Then in production, artists in each department can avoid wasting time trying to find the right creative ballpark, and instead have the clear direction that lets them focus on hitting the home runs they were hired for.

Story Artist ≠ Storyboard Artist

This is one of the most commonly confused titles, and understandably so because of the wording. It does however lead a lot of trouble for productions who don’t understand it. If your story cement is solid and you just need it illustrated for production, hire a storyboard artist. If your story cement is wet and you’re still writing and planning, hire a story artist.

STORY ARTIST

(Story Dept)

Works in the Story Department, as a writer who also sketches rough boards as part of writing and re-writing scenes.

Typically you have a head screenwriter, and a head of story, then what would normally be the assistant writers in the room for live action are “Story Artists” in feature animation, meeting in the story room to discuss the story, pitch ideas, and give feedback on sequences. Then instead of typing scripts, they sketch.

Another title could be “Story Director” or “Sequence Director” as Story Artist roles also mirror much of the role of an Episode Director in television animation.

STORYBOARD ARTIST

(Art Dept)

Works in the art department, as an artist who focuses solely on illustrating a locked script, preparing to shoot. This focuses on making ‘final boards’ that are ready to be put into production, usually on a live set for shooting day, or to give an FX company to work from.

In Live Action they are commonly used for complex or expensive fx shots, while in TV animation they are often doubling as ‘layout’ drawings that animators can work from as an exact model and ‘visual contract’ between studios being contracted out to do the actual animation and production work.

There is a version of this in Feature Animation that existed for 2D called the “Workbook pass” which was a final, more illustrated version of the boards ahead of production. The Workbook pass was slowly replaced in CG with an animatic.

Is it always this clear?

Almost NEVER! That’s one of the biggest problems of the job is that there are simultaneously shows who use story teams as writers, and others who all but hide the script from them. “Story Driven” shows that use their Storyboard Artists as Story Artists, and vice versa.

The titles are carelessly and constantly swapped from studio to studio, project to project, to the point that nobody knows what to expect from each other. This causes all kinds of problems down the line with expectations on both sides completely out of alignment.

Imagine your surprise after screenwriting for years as a story artist, then thinking you’ve taken another job to continue growing in that direction, only for your story supervisor to act surprised when you begin doing the very thing you took the job to do, and showed examples of to get it.

Or as the studio expecting your story artists to write, but realizing they don’t have that experience you assumed they would. Sure, they can learn it on the job, but you need these scenes yesterday!

Clearly defining the roles and definitions is something we really need in order to foster efficient workflows and career progression while avoiding unnecessary churn & burnout.

Who Says?!

Any artform is full of as much craft and discipline, as it is opinions and conjecture. As it should be. I’ve tried to only take advice from the people I saw proving their talk with the walk of their work.

Fwiw, my introduction to this was training as a story artist with founding members of Pixar’s story department Joe Ranft, and Rob Gibbs back in the mid-90’s, both of whom have sadly passed away, but were instrumental in not just inspiring a major direction of my own life as an artist, but helped lay the groundwork of Pixar’s historic rise in a record setting string of back to back hits under the mantra “Story is King”. For my part, there’s nobody more qualified to define it than they did.

I’m very grateful to have learned from them, and then to continue learning from some of the most successful people in story over the past few decades at each studio. So, my definitions echo what I learned from all these legendarily talented storytellers, along with what I’ve seen work in my own experiences doing it.

Evolution of the Job

Like any industry evolves, the role of the jobs evolve too. Whether we write, sketch, pitch, board, act, edit…the purpose of the job is to allow us to create, iterate, and develop a story and how it’s told in the language of our medium, which in the case of a story artist, is creating characters and worlds with visual storytelling. Pictures and Sound. Timing and Dialogue. Cinema.